When executives are first introduced to Sales Process Engineering, they naturally assume that this new approach to sales will be tough on salespeople.

But, interestingly, it tends not to be. Salespeople adapt quickly. They enjoy working in an environment that’s custom-engineered to multiply their productivity.

The individual who really suffers as a result of this transition is the Sales Manager.

While the Sales Manager may approve of SPE in theory, in practice, they find themselves presiding over an environment they no longer understand and, as a consequence, an environment they are ill-equipped to manage. Without executive foresight, this is likely to result in the sales function becoming rudderless at the very time you are trying to chart a new course.

This final chapter discusses management requirements of the new model – as well as the special requirements of the transition to SPE.

Why does management exist

It doesn’t hurt to start our discussion by reminding ourselves why management exists.

We touched on this in Chapter 2, when we recognized that division of labor creates the requirement for management. When team members narrow their focus to a tiny sub-set of tasks, the responsibility for the synchronization of the environment as a whole needs to shift elsewhere.

Enter, the manager!

In practice, managers tend to be responsible for more than just the internal synchronization of their functions. They are also responsible for:

- Maintaining the integrity of their domains: this translates into practical activities like hiring and firing, controlling expenses, ensuring procedural compliance and so on

- Managing the interface between their functions and other organizational functions

In the modern organization, management has become stratified:

All but the smallest organizations evolve three levels of management – each with quite a different set of responsibilities:

- Line management: the direct management of individual contributors (supervision)

- Functional management: the management of a department

- Executive management: responsible for long-range decision making and the architecture of the organization

Management and the standard model

In traditional environments, we tend to encounter managers at both the functional and executive levels.[i]

If the organization is large enough to have an executive-level manager with sales responsibility (a VP of Sales and Marketing, for example), we typically find that these individuals are very capable – and ideally placed to champion the transition to the new model.

However, where functional managers are concerned (the standard-issue Sales Manager), we tend to find that these individuals are either quite poor or quite exceptional (and they rarely fall anyplace in between!).

We have the design of the standard model to blame for this.

As we’ve discussed previously, the hallmark of the standard model is that salespeople operate as autonomous agents. Of course, autonomous salespeople and sales managers are two incompatible concepts. Salespeople either march to the beat of their own drums, or they don’t.

Sales managers develop two methods for coping with this conundrum.

The first, most common, method is to avoid managing salespeople in the traditional sense of the word. The sales manager who adopts this approach tries to establish themselves as a coach or a trusted advisor to salespeople. When there’s a requirement for the sales manager to exercise some control, they will attempt to exchange some of the goodwill they have established with salespeople for a concession or two. They’ll call-in a favor, in other words.

The second method is to pay lip-service to salespeople’s autonomy but to ignore it in practice. The manager who adopts this approach will use the force of their personality to overpower their team members’ autonomous ideals and rule them with a mix of fear and grudging respect.

Sadly, a manager who has adopted the first method will find the transition to the new model very difficult (if not impossible). Unfortunately, their history with the sales team has resulted in the establishment of a number of negative precedents. Even if salespeople can put these precedents behind them, the sales manager very often can’t.

The best approach, therefore is to transition the sales manager into another role. If the sales manager was awarded the position because they were a capable salesperson, it may make sense for them to return to sales (and, often times, this will actually be their preference!).

A sales manager who has adopted the second method is well placed to transition to the new model – and will often be a major advocate of the new direction. The danger with these individuals is that their firebrand-tendencies can often spill-over into their interactions with other functions (poisoning the organization as a whole).

If you have a sales manager who is mature enough to rule their team like a tyrant and to interface with other departments like a diplomat, then this individual is a rare find indeed (and should probably be on the fast-track to the executive suite!).

Management requirements of the new model

The new model is structurally different from the old one – and this tends to have quite an impact on management requirements. For example:

The centralization of customer service, and of a significant number of sales activities, results in a larger phone-based team – and that team will benefit enormously from close supervision.

The reduction in size of the field team and the elimination of most (if not all) regional sales offices will significantly reduce the political challenges associated with the management of a traditional sales team.

And the centralization of the generation of opportunities, along with the more sophisticated promotional function that’s required to achieve this, will increase the complexity of the overall sales machine.

In summary, then, the transition to the new model will tend to result in:

- A requirement for line management – that didn’t previously exist

- A requirement for fewer functional managers – with all sales activities centrally scheduled, silos cease to exist

- A significant increase in the scope of functional management (or the emergence of a requirement for executive management) – the head of sales is now managing a more complex machine

The boundaries of the sales function

It’s hard to progress this discussion without first defining the boundaries of sales. Specifically, we need to consider whether customer service, marketing and project leadership are to be considered part of the sales function?

My short answers to these questions are “yes, sometimes”, “yes, mostly” and “no, never” respectively!

Technically, customer service should be regarded as part of operations (not part of sales). The processing of repeat transactions, the generation of quotes and the resolution of issues are all operational activities.

However, customer service operators work in an environment very similar to that of inside sales personnel. They work in cubicles, illuminated by the glow of computer monitors, and they spend most of their time talking with customers via their headsets.

This means, in practice, that unless your customer service team is large enough to warrant its own dedicated supervisor, it makes sense to integrate customer service with your other phone-based sales personnel. This way, you can justify adding a capable inside sales supervisor to manage the team as a whole.

Where marketing is concerned, either some or all of marketing should live within sales and, again, size is the main consideration.

It’s useful to consider marketing as two discrete functions. There’s marketing communications (or marcoms as it’s typically called) and promotions.

The former involves the preparation of general marketing materials, the maintenance of web properties, investor relations and so on. And the latter involves the execution of promotional campaigns expressly designed to maintain your sales team’s opportunity queues.

The former is primarily concerned with marketing infrastructure and is typically engaged in longer-lead-time initiatives. The latter is scrambling to run campaigns and replenish fast-depleting opportunity queues.

The two functions have different perspectives and operate at quite different cadences.

Our position is that promotions should always be a part of sales and that marcoms may or may not be, depending upon the size of that function.

In a small organization, it’s likely that the promotions would consist of just a campaign coordinator (and, most likely, a part-time research analyst) – and that all other marketing would be outsourced.

In a larger organization, the promotions team might contain a number of specialists (campaign coordinators, research analysts, event coordinators, data analysts, etc) and this team would likely commission all necessary inputs from the marketing department (marcoms).

So, for the purpose of our discussion, we’ll treat (just) promotions as part of the sales function. (Although we will drop-in on marketing again when we discuss executive management.)

Project leaders must neither be a part of sales nor a part of production. As discussed earlier, their very reason for existence is (in part) to manage the necessary tension between these two functions. Accordingly, project leaders can belong to your engineering function, if you have one; and if you don’t, project leadership should be a department of its own (assuming you need it, of course).

Line management

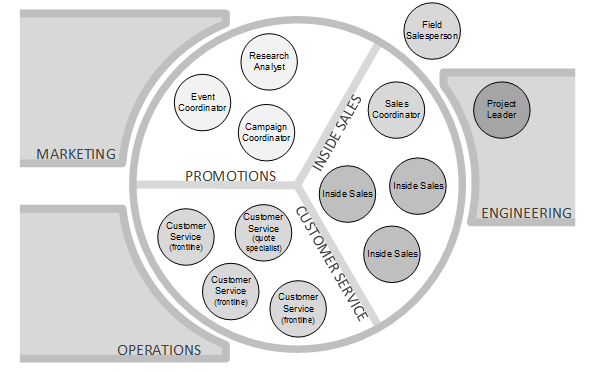

The following diagram shows the individual contributors in a typical sales environment. We have an inside team, consisting of promotions, inside sales and customer service; and we have two external team members, a salesperson and a project leader.

In this diagram, we are treating sales coordination as a sub-set of inside sales – which makes sense when you have both functions.

This diagram pictures the key roles (individual contributors) within the

sales function, as well as three adjoining functions

In a sales function of roughly this size (headcount), it would make sense to have one supervisor manage the entire internal team.

As the sales function grows, you can allocate dedicated supervisors, first, to customer service and, then to promotions. Because the research analyst role consists of repetitive, (mostly phone-based) work, it’s better to have your research analyst supervised by the inside sales supervisor (although the content of their work should still be determined by promotions).

The sensitive question now is, who manages the field salespeople?

Well, of course, in the new model you are likely to have only a fraction of the field salespeople you had previously, meaning it’s quite likely (per the diagram above) that your field team is nowhere near large enough to justify a field supervisor.

This means that your field salespeople will need to answer to whomever is leading the sales function as a whole.

Functional management

As suggested earlier, we can see that the sales manager’s domain looks quite different in this new model.

In the standard model the sales manager oversaw a bunch of field salespeople – and that was about it.

Now, however, our sales manager has just one field-based report (at least in the model above) and the rest of their team is inside. This inside team contains three quite distinct specialties (and four additional sub-specialties).

And, as has been a central theme of this whole book, in the new model, sales functions quite differently. Sales is now a machine – and the success of that machine is more a function of its internal coordination than it is of individual feats of heroism.

This requires a different approach to management: more lieutenant colonel and less Wolf of Wall Street!

As you may already be suspecting, in a sales function the size of the one pictured above, the requirement for both an inside-sales supervisor and a sales manager is questionable. It might be better, in these circumstances, to either have a sales manager manage the entire sales function (including promotions and customer service) or to have no sales manager at all and have the field sales person answer directly to a senior executive.

If you do not already have a capable sales manager, with a sales function of this size, the latter would be preferable. It is certainly less risky to employ a supervisor for the inside team and have a senior executive (ideally the CEO) manage the field salesperson than it is to gamble on a sales manager.

This is particularly true if you are in the process of transitioning from the old to the new model. A new sales manager is much more likely to try and recreate their previous sales environment than they are to dutifully build the environment described in a book that they agreed (somewhat reluctantly) to read during the recruiting process!

Executive management

As mentioned earlier, larger organizations will typically have a VP of Sales (or VP of Sales and Marketing). In smaller organizations, this responsibility typically rests on the shoulders of the CEO.

Such a person is responsible for the overall design of the sales function and the integration of the sales function with the organization as a whole.

In a mid-sized organization – one that has grown large enough to justify this position – I would suggest expanding the scope of this role to include the whole growth value chain: specifically, new-product development, marketing and sales.

This is important because, sales cannot continue to function effectively, for any reasonable period, without the tight integration of NPD and promotions. The absence of this integration is one of the most common (and persistent) problems I see with mid- to large-sized organizations.

Accordingly, my preference would be to title the executive-management role: VP of Growth (or something similar).

In summary

In summary, then, if you are transitioning your organization from the standard to the new model – and if your sales function is small, but growing – I would expect to see the following:

You commence by adding a supervisor to oversee your fast-growing internal team (inside sales, promotions and customer service).

Your CEO assumes responsibility for general sales management and for the direct management of your field-based salespeople. This is likely to require that your CEO performs occasional, high-value sales calls to assist your field salespeople with major opportunities. Your CEO also fills the VP of Growth role, which requires that they take a special interest in NPD.

As you grow, you add a customer-service supervisor and you nominate a team lead within your promotions team (promotional coordinator). At some point, your CEO will add a sales manager, so they can take a back from functional management responsibilities (including joint calls with salespeople and running regular sales meetings).

Ultimately, your CEO might choose to hand-off the VP of Growth responsibilities – or they may prefer to hand off other responsibilities and maintain focus on this critical role.

How to manage sales

What follows is a general discussion of how to manage sales. This section contains advice for both supervisors and functional managers.

Effective sales management starts with a decision to manage – in a true sense of the word. And this for many managers (and executives) is the toughest decision of all. In the new model, the manager must shoulder a number of responsibilities that have traditionally been delegated to salespeople.

In the traditional model, salespeople are responsible for generating sales and sales managers are responsible for supporting them to the extent they need support (and staying out of their way when they don’t).

In the new model, because sales is now a team sport, it is no longer possible for salespeople to single-handedly generate sales – anymore than it is possible for a single football player to win a game.

This means that management must own the responsibility for sales outcomes, rather than salespeople. And management must be responsible for both the overall design and the day-to-day supervision of each of the components of the sales machine.

Preconditions for sales management

A decision to manage isn’t the only precondition. The following are also critical requirements:

- A goal and a set of necessary conditions

- An understanding of the dynamics of the sales machine

- A management method

- Management information

Goal and necessary conditions

In Chapter 4, we discussed that most modern organizations benefit from the system constraint being maintained (by sales) upstream from either production (make to order) or engineering (engineer to order). In these circumstances, the goal of sales should not be to sell as much as possible! The goal should be to maintain the size of the order book within an acceptable range.

Sales management must know exactly the number of days’ worth of work (and the mix of work) that should be maintained in this buffer. And, of course, the sales machine must be engineered with these requirements in mind.

In addition to the goal, sales management must have an explicit understanding of necessary conditions (conditions that must be maintained, in order for the achievement of the goal to be valid.) For example, sales management needs to know the allowable acquisition cost (the maximum that can be spent on promotion in order to win a new account).

Dynamics of the sales machine

Obviously, it’s not possible to manage a machine unless you understand its inner workings. Accordingly, sales management must have a profound understanding of the entire sales (and promotional) value chain. They should understand the (often circuitous) path that $1 in promotional spend follows in order to be transformed into an account worth thousands (or tens of thousands) of dollars (lifetime value).

They should also understand that theirs is not an infinite capacity environment. They should appreciate that each team member has a maximum-sustainable capacity – and that most, if not all, should not be allowed to be fully activated for extended periods of time.

Management method

The organization as a whole should have a formal approach to management – a standard process and a set of minimal requirements. Sales, obviously, should inherit this method.

In the unhappy event that the organization doesn’t have one, sales management will have to lead by example.

My preference is that this method is simple. It should require that management participate in a small number of regular – and high-value – meetings. And it should pay as much attention to what managers don’t do as it does to what they do do! Specifically, it should ensure that managers always have protective capacity. (A fully-burdened manager is an ineffective one.)

Management information

It should be obvious that management needs data to manage. A manager without data is a fool with an ego (and, as far as fools go, the ones with egos tend to be the most insufferable!).

When I declared above that management must have a profound understanding of the sales value chain, the word profound was intended to indicate that management is required to understand the cause-and-effect relationships within the sales function at a mathematical level.

The management information system should take two forms. It should provide sales data in a form that enables management to ask questions of it (hence my love of pivot tables)[i]. And it should allow the manager to expose whatever (small number of) metrics it makes sense for team members to be focusing on at any given moment in time.

In my opinion, sales management cannot get by without a basic (high-school level) understanding of statistics. If your sales manager does not have this, you must insist that they remedy this problem immediately. A sales manager without an understanding of statistics is like a chef who lacks an appreciation for food hygiene (both will look the part but no good will come of either in the long run!)

Line management: managing salespeople

Now we have those management preconditions in place, let’s talk about how to actually manage salespeople (field and inside salespeople).

Here’s a three-step formula:

- Conviction

- Activity

- Deals

Conviction

Your sales manager must start with conviction. Conviction that your offering is saleable – and that it can reasonably be sold by your sales team. I don’t mean fake conviction. I mean the kind of quiet conviction that comes from certainty (as in I’m convinced the sun will rise tomorrow).

Once your sales manager has this conviction they must ensure that at least the opinion leaders within your sales team have it too. Now, you don’t get this conviction by faking it. You get it by proving – beyond reasonable doubt – that your offering is actually saleable – and that it can be sold by your sales team!

If opinion leaders within your sales team lack this conviction, your sales manager must make calls with them to, initially, demonstrate how it is done and then, ultimately, to ensure that they do it successfully.

If your sales manager lacks this conviction then, guess what? You must make calls with them to, initially, demonstrate how it is done and then, ultimately, to ensure that they do it successfully.

If you are a VP of sales, this is a responsibility that you clearly can’t dodge. Similarly, if you are a product manager, the CEO or the founder, the buck stops with you! Shine your shoes, install your sales manager in the jump seat and go make some sales (either in person or by phone).

I’m serious.

If you are a senior executive you should be able to sell a saleable proposition, simply by virtue of your seniority (and if you’re the founder, you shouldn’t even need to shine your shoes – a clean pair of flip-flops should be sufficient!)

If you’re a senior executive (or the founder) and you can’t sell your offering, you better face reality. Your offering is not saleable, your system constraint is not in sales and you’re reading the wrong book![ii]

Conviction is important because, without it, your sales manager has no authority and simply cannot manage.

Do not skip this step.

Activity

We’ve already discussed that activity – or more specifically, meaningful selling conversations – is the primary driver of sales.

Activity alone doesn’t guarantee you sales but an absence of activity is a guarantee of an absence of sales.

For this reason, the sales manager should treat activity as a necessary condition. Each salesperson must perform a fixed volume of sales activity, day-in and day-out.

If we’re dealing with field salespeople, this is more of a process- than a people-management issue. In the new model, it’s the responsibility of promotions, in conjunction with salespeople’s coordinators, to ensure that field representatives’ calendars are fully booked (four appointments a day, five days a week). Typically, you’ll find that, if field salespeople wake each day to discover a day full of pre-scheduled meetings, they will be quite happy to perform them.

During the transition to the new model, management may need to act to ensure that salespeople do not quarantine working hours (for personal or off-grid business activities).

Where inside salespeople are concerned, it’s critical that your sales manager stipulates an optimum daily volume of meaningful selling conversations (as well as an allowable range). Typically, in an inside-sales environments this will be somewhere north of 30 meaningful conversations a day. In such an environment, a meaningful selling conversation should be defined as any conversation where the sales proposition is discussed, as opposed to a simple connect or an agreement to call back later.

If inside salespeople use email (or chat) to sell, you might like to use the term meaningful selling interaction. Either way, all interactions should be tracked in CRM, and coded, to enable interactions of the meaningful variety to be counted.

It’s important to note that activity volume is a necessary condition, not the goal. Accordingly, it should be expected, and not celebrated. The only exception is when you are attempting to shift activity levels to a new level.

In inside-sales environments there are a couple of techniques you can use to ensure consistent activity volumes:

- Protected calling blocks: these are periods of time (typically one-hour blocks) where the team sprints to achieve a minimum volume of meaningful conversations

- The desk-is-for-working rule: this is a stipulation that, if the salesperson is at their desk, they are on the phone (it is not a stipulation that the salesperson should spend all day at their desk, however!)

I like both of these techniques because they recognize that people are not robots. They perform best when they can sprint and then relax.

The inside sales team of one of our silent revolutionaries (in country Australia) works in a mezzanine above their plant. All the sales team members like to lift weights (as do I) – and they have a mini gym on the plant floor beneath where they work.

Their sales manager’s rule is that working hours are either for banging-out calls or squeezing out reps – either is fine by him (and by me)!

Deals

If your salespeople have conviction – and if sales activities are consistently high – deals will flow.

If you’d like them to flow faster, then (and only then) you can focus on sales techniques (skill development).

Actually, I should say, when all sales performance prerequisites are in place, your sales manager MUST work with all salespeople on skill development (at least weekly).

The only time that a salesperson should be excused from sales drills is if management agrees that they are a sales master and if their sales performance (relative to the team as a whole) is consistently in the fourth quartile.

I use the term drills deliberately. Day-to-day sales training should be similar in design to athletic (or military) training – as opposed to classroom-style instruction.

Additionally, this day-to-day training should be the responsibility of your sales manager.

Sales drills should consist primarily of role-playing exercises. Role-playing is analogous to sparring in boxing (and other fighting arts). The objective is to build muscle memory: to convert exchanges that might otherwise feel unnatural into reflex. Accordingly, repetition is the key to mastery.

In most cases, it is impractical to script entire sales conversations (the obvious exception is appointment-setting calls). My preference, instead, is to:

- Divide the ideal selling conversation into a set of steps

- Script the transitions (or bridges) between steps (including asking for the order) [iii]

During drills, the scripted portions of sales exchanges should be delivered word-for-word as per the script. That’s the reason for the script in the first place! Normalizing the words, enables the team to focus its attention on delivery.

On sales managers who don’t

Now, I know that most sales managers don’t manage like this. And, to some extent, that’s understandable. After all, in the standard model, salespeople are supposed to be autonomous.

But that does not alter my conviction that this is how you manage salespeople.

It’s how I was managed when I joined the insurance industry many years ago. And it’s how I managed my own team of salespeople. Then, when I advanced to a head of sales position, it’s how I insisted my sales managers manage their teams. (In spite of the fact that our salespeople were technically autonomous, we didn’t allow that to prevent us from terrorizing them into making stupendous amounts of money!)

To be frank, I’m horrified by what passes for sales management in most organizations I visit today. The truth is that most sales managers meet with their teams infrequently, deliver no training and spend most of their time on their own sales calls.

The new model provides sales managers with both information and control: it’s absolutely critical that they embrace both. And it’s absolutely critical that you insist that they do!

Performance is not optional!

On the subject of assuming control, one of the benefits of eliminating sales commissions is that it enables management to make it clear that performance is not optional.

If a salesperson is on your team they must sell to stay there (just as a welder on your shop floor must weld). It’s true that sales is a more uncertain environment than production, but that’s why it’s important that your sales manager possesses a high-school-level understanding of statistics.

Statistics provides the tools your manager needs to collapse the uncertainty and arrive at certain assessments of individual’s performance.

The easiest way to evaluate salespeople’s performance is to calculate the Throughput (contribution margin) they generate, on average, for each meaningful conversation they perform. You can then compare individual salespeople with their colleagues.

The benefit of assessing salespeople on a relative basis is that it allows you to control for factors outside their influence (e.g. the efficacy of promotional campaigns, your estimating team’s pricing policies and so on).

Sales management mechanics

Because sales management is a supervisory (line-management) role, the manager should be co-located with – and work closely with – their team.

They should not own any sales opportunities and they should not perform any calls or appointments unless they are doing it in the company of one of their salespeople. As should be the case with all managers, most of your sales manager’s time should be unscheduled. They cannot effectively supervise their team if they are busy.

Aside from general (deliberately) unstructured supervision, your sales manager (and all line managers) should perform the following:

- A daily, stand-up work-in-progress (WIP) meeting – more on that in a minute

- Periodic one-on-one discussions with team members

- Joint calls with field salespeople (or joint-calling sessions with inside salespeople)

- Recruiting

Supervising the internal sales and customer service personnel

As discussed earlier, it often makes sense to combine inside sales, customer service and sales coordinators into one internal sales function. This results in a large enough team to justify the addition of a dedicated sales manager.

Managing the sales function

As is suggested by the title of this book, the sales function is a complex machine.

This machine contains multiple teams of specialists (promotions, inside sales, sales coordinators, field salespeople and supervisors – and, sometimes, customer service).

The head of sales is responsible for ensuring both the internal and external synchronization of this machine.

Internal synchronization means ensuring that these various teams work in harmony and external synchronization means ensuring that the sales function integrates effectively with engineering, production, finance and other departments.

External synchronization was discussed briefly in Chapter 4, when I introduced Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints. The basic idea is to start with an understanding of which of your departments is supposed to be your organization’s constraint – and then to make resource allocation decisions so as to ensure that it stays that way. For example, in a make-to-order environment, the role of both engineering and sales is to maintain an optimally-sized order-book upstream from manufacturing. This means that sales and engineering need protective capacity (enough capacity to sell and engineer at a faster rate than production can produce). It also means that these functions should ease off when the order book is full and sprint as it starts to diminish in size.

Internally, it makes sense to apply a similar programming approach to sales. In short, this involves:

- Nominating a team as the internal pacesetting resource (a virtual constraint)

- Ensuring that other teams subordinate to the pacesetting resource

- Maintaining a buffer of work up-stream from the pacesetting resource and exploiting this buffer as a source of management information

It makes the most sense for your internal pacesetting resource to be either your field-based salespeople or your inside sales team (typically the latter, if you have both).

This means that promotions (and sales coordinators) should be responsible for ensuring that queues of work up-stream from salespeople are maintained at their optimal sizes – and that other teams process their work quickly to ensure that they don’t become bottlenecks.

If you have read The Goal (Goldratt’s master work), the preceding passage will make sense. If you have not, I urge you to remedy that urgently! Sadly, a comprehensive introduction to The Theory of Constraints in general, and the Drum-buffer-rope approach to planning, in particular, is beyond the scope of this book.

Manage for consistency, not peak output

You may have noticed that this discussion elevates synchronization above the pursuit of peak results.

One colossal mistake we made back in my sales-management days was that we managed sales for peak output.

We’d run regular sales competitions (sometimes with offers of overseas holidays for members of the winning team) and we’d congratulate ourselves on our ability to hit new sales highs as our promotions became more elaborate and our prizes more generous (and expensive).

In retrospect, though, it’s clear that all we did with our focus on peak output is move revenue around. On one occasion we sent an entire (Australian) sales team on an all-expense-paid vacation in Las Vegas (such was the magnitude of their sales results!). However, when they returned from their vacation they went from the best- to the worst-performing team – and it took the team months to spool back up again.

The net result in this – and other cases – was that we exchanged consistent sales for occasional sales bonanzas and, on average, reduced the profitability of the business.

This, needless to say, is not entirely clever.

Your sales manager should manage sales just like a production environment. The goal should be to generate a steady volume of sales, month-on-month. Record months are only worth celebrating if it’s likely that a new normal has just been achieved.

The magic of the 15-minute, stand-up WIP meeting

One of the first things I discovered when I emigrated to the USA was that pretty much every manufacturer runs a short, stand-up WIP meeting at the start of every shift.

(Similarly, most all software environments run some variation of SCRUM meetings – which are similar in both design and function.)

We were quick to recognize the enormous value in these meetings and replicate them in customer service and internal sales environments. WIP meetings are an extremely effective way of synchronizing the work within each your teams – particularly work that is too granular to plan in a formal scheduling system – but, if you stagger them, WIP meetings are also an effective way of synchronizing the sales function and, indeed, the organization as a whole!

As well as being effective, WIP meetings are efficient. They consume very little time and they provide management with insight that would otherwise be very difficult to gather.

A WIP meeting is a brief and carefully choreographed discussion of work in progress. It should be conducted at exactly the same time every day and each meeting should have exactly the same agenda.

Our normal approach is to stagger WIP meetings, working backwards from production – and to have a participant in each meeting attend the next to update the upstream team on notable outcomes. Most of our quiet revolutionaries will have a team lead run each WIP with the responsible manager participating (and asking tough questions!).

These meetings are always short (15-30 minutes) and participants always stand for the duration of the meeting. (There’s no such thing as a 15-minute, sit-down meeting!)

Here’s a typical agenda:

- Review the status quo

- Total volume of open jobs (or sales opportunities)

- Distribution of work between team members

- Status of queues (particularly the pacesetter’s buffer)

- Review late-stage work

- Opportunities that should be closing imminently (or should be abandoned)

- Customer service tickets that are in danger of running late

- Agree on action items (and disband)

General sales meetings

In addition to daily WIPs, you must convene a weekly sales meeting that includes sales training (and role playing).

If you have field salespeople, a daily, stand-up WIP tends to be impractical. Accordingly my preference is for salespeople to attend this weekly sales meeting, along with their sales coordinators and your promotional coordinator. (Remote salespeople should attend via video conference.)

These sales meetings should be split into three components (with your promotions coordinator leaving after the first):

- Review the status quo (as per WIP meetings)

- Review late-stage opportunities

- Sales training

Where the review of late-stage opportunities is concerned, your sales manager must ask tough questions to gain insight into exactly how salespeople are conducting themselves on calls and to enable team members to offer each other counsel.

Sales training should consist primarily of role playing (as discussed earlier).

Management information

We’ve discussed management information earlier, but an additional note is warranted.

Because most of management’s responsibilities are being discharged in WIP meetings, it makes sense to design your management information system around your WIP meetings.

This means your MIS should deliver answers to the following questions:

- How large are our queues of WIP?:

- How many days’ worth of appointments are scheduled in our field salespeople’s calendars?

- How many days’ worth of sales opportunities are queued up-stream from each sales coordinator and inside salesperson

- How many days’ worth of prospects are in queue, awaiting promotional campaigns

- How productive are our salespeople?:

- What is the average Throughput generated from each meaningful selling interaction

- What is the velocity of our sales opportunities?:

- How many days are opportunities sitting at each stage in our sales workflow?

- What is the likelihood of late-stage opportunities converting (into deals) in upcoming months?

In addition to this sales information, promotions needs to know:

- What return are we earning on our promotional spend (by campaign)?

- What does it cost (in promotional expenditure) to add a new contact to the house list?

- What does it cost (in promotional expenditure) to generate a sales opportunity?

Forecasting (hocus-pocus with a dollar sign!)

I can’t complete a chapter on management without touching on forecasting.

Forecasting is an activity that consumes inordinate amounts of both sales managers’ and salespeople’s limited capacity. And, in most cases, this time is completely wasted.

Actually, the reality is worse than that.

In most cases, the forecasting ritual generates misinformation that poisons the rest of the organizations and damages the relationships between sales and other functions. Forecasting, as it’s typically practiced, reminds me of stories of Cargo Cults on some Pacific Islands after World War II.

The relatively primitive lifestyles of these islanders were interrupted by Japanese aircraft dropping large supplies of clothing, medicine, canned food and tents to support the Japanese war effort.

Some of these supplies were shared with islanders, in exchange for their assistance.

After the war, when planes and their valuable cargos disappeared, some islanders took to imitating the rituals they’d observed the Japanese performing. They carved headphones from wood and wore them while sitting in fabricated control towers. And they waved landing signals while standing on abandoned runways.

The forecasting ritual imitates the objective (evidence-based) approach to management that sales leaders observe in other parts of the modern organization. But it fails to recognize the limitations of forecasting.

The standard approach to forecasting

The standard approach to forecasting is very simple: aggregate risk-adjusted estimates of future revenue from all salespeople and distribute the resulting number (the sum of all salespeople’s estimates) to the rest of the organization to inform decision making.

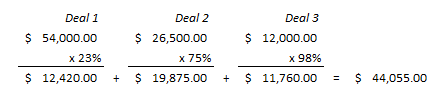

So, if a given salesperson is working on three opportunities that they believe they will win next month, their calculus would look something like this:

In case you’re wondering where the weighting comes from, in many cases salespeople simply supply a percentage that feels right. In other cases, this number is informed by the stage the opportunity is at in the opportunity management process. The latter approach only provides the perception of objectivity, however, because, it’s generally the salesperson’s opinion that determines when opportunities advance from one stage to the next!

In some cases, sales managers will intercept these numbers and apply a discount to them to compensate for salespeople’s natural optimism.

The problem here is fairly obvious. When you consider the incredible uncertainty baked into each of these numbers, you would need a massive sample size in order to create an estimating process that has any hope of yielding a meaningful number.

And, in most cases – because of the design of the standard sales model – salespeople have only a handful of opportunities under management at any point in time.

A better approach

A better approach is to simply recognize that uncertainty and sample size conspire to make a statistical approach to forecasting impractical.

Our quiet revolutionaries have abandoned statistics (and the veneer of certainty) in favor of a more honest scenario-based approach.

Here’s how that approach works:

- Ensure stages are aligned with objective customer behaviors

- Ignore early stage opportunities altogether

- In each sales meeting, review late-stage opportunities as a team and agree to allocate each to one of three categories:

- Possible

- Probable

- Highly likely

- Agree on the month in which each deal will likely close (if, indeed, it does)

- Use this data to generate three month-by-month scenarios:

- Worst case (pessimistic, but not paranoid)

- Mid case

- Best case (optimistic, but not foolhardy)

- Make this data available (in summary form) to other departments – and refuse to collapse the dataset into a single number

In most cases other managers will appreciate the sales department’s newfound honesty. If managers do push back, it’s important to explain that collapsing these scenarios into a single number will destroying information, as opposed to creating it!

Considering that uncertainty is actually an attribute of the environment (and not the sales manager), a set of scenarios will actually be more valuable to finance and other functions. This is because each decision that a manager makes has its own risk profile.

In some cases managers must act primarily to avoid downside (e.g. to avoid breaching customers’ service-level agreements) and in other cases their motivation is the pursuit of a gain of some kind. In each case, managers will pay greater attention to one of the three scenarios.

Parting words of advice

With this book drawing to a close, it’s over to you now!

I’d like to leave you with some sage advice to guide you on your journey (notwithstanding the many pages of good advice dispensed thus far!)

So, here we go.

Remember the goal

Remember, the goal of a business is to make money (now and in the future). Making team members (including managers) happy is a necessary condition. Necessary conditions must always subordinate to the goal.

So, start with a clean sheet of paper and design your ultimate sales function without consideration of your existing team – and then determine how to transition to that sales function.

If you attempt to do both, simultaneously, you will end up designing what you already have – and your improvement initiative will be limited to adopting (and degrading) a new sales and marketing lexicon.

Customize your application of SPE, not the four key principles

If you must customize one of the applications of SPE described in this book, be sure that you do not violate any of the key principles.

For example, if you partner your salespeople with sales coordinators and then decide – for cultural reasons, perhaps – that you will retain performance pay for salespeople, then you are in violation of one of the key principles.

Specifically, you are not centralizing scheduling if you are simultaneously paying one or more team members on a piece-rate basis. This one concession will be the undoing of your whole initiative. If it’s not clear to both your salesperson and your sales coordinator who owns the schedule, then you will have conflict between them. This will result in your salesperson reclaiming their autonomy and it will force your sales coordinator to either shrink into the role of hapless assistant or (more likely) to resign.

Commit. Absolutely.

If you are going to make the kind of fundamental changes that are required to implement SPE, you should only proceed if you are prepared to commit (absolutely) to the future state.

If you are not fully committed, the sceptics among your team will sense it and they will either resist passively or they will actively undermine the change initiative.

If you are not fully committed, wait until you are. Alternatively, design a less ambitious future state (assuming it’s possible to do that without contravening the point above!)

On the subject of commitment. If you’re going to bet, bet big. Not big enough to risk the company – but big enough to prove that you mean business and big enough to ensure that your change process doesn’t take so long that it dies on the vine.

For example, if you’re building an inside sales team and your new team has just one person in it, you’re not really building an inside sales team, are you? If you want proof of concept, you (or your executive assistant) can spend a day banging the phones and monitoring the reception you get. But, once you have proof of concept, make a meaningful commitment.

Obsess over activity levels (MSI)

People ask me often, “What should I measure?” – no doubt, expecting me to reel off a list of metrics. The truth is, early in your transition to the new model, you should measure one thing only – and you should obsess over this number!

The metric (as I’ve already discussed) is sales activity or, more specifically, your volume of Meaningful Selling Interactions (MSI).

No matter what else happens, this number must go up – week on week. And it certainly must go up each time you make a change to your sales function.

Realistically, obsessing about your volume of MSI’s will force you to be mindful of other metrics too (the size of opportunity queues, for example) but you don’t have to worry about that right now. Obsess over your volume of MSI’s and everything else will look after itself.

Now, I know that the goal of a business is to make money – and your MSI number doesn’t have a dollar-sign in front of it! But that’s okay. This is a change initiative we’re talking about here, not business as usual.

Because you’re making radical changes – and because it takes a long time for the impact of those changes on sales numbers to manifest itself – it’s critical that you have a faster feedback loop. You need a proxy for money. And MSI is it. You better believe it!

Inside-out, not outside in

Years ago, a Director of Sales at a quiet revolutionary in Portland, Oregon told me that SPE resonated with his management team because they’ve always believed in an inside-out approach to business.

I appropriated that term on the spot – and I’ve been using it ever since.

Regardless of how many activities you perform in the field, SPE is fundamentally an inside-out approach to sales. Sales opportunities are originated inside. They are owned inside. All activities are planned inside. With SPE, the locus of sales is definitely inside.

Accordingly, when you are planning and implementing SPE, be sure to start inside and work out – and not the other way around. More specifically, start at the factory door and work backwards.

A second ago, I hung the phone after counseling an executive who just embarked on this journey. She was concerned that it wasn’t possible to rapidly upskill her customer service team with the capabilities required to manage inbound orders, generate quotes and handle customer issues.

I pointed out to her that this isn’t the emergency that it seems to be. Fact is, someone in her organization is doing all that stuff right now. I encouraged her to identify the activity that occurs (or should occur) immediately prior to jobs entering production. (Often times, this activity is what we call prerequisite management.) I advised her to first have her customer team acquire absolute mastery over that activity. Once this has been achieved the next activity in sequence can be transferred. And then the next.

By the time this executive has a truly robust customer service function, she’ll have a much stronger base to build on and she’ll be much more confident taking her next steps.

This approach is the exact opposite to most sales improvement initiatives. Typically, sales improvement is more likely to start with a new comp plan or an expensive lead-generation campaign.

Ask for help

It’s true that SPE is a radical departure from standard practice. But that doesn’t mean that you’re alone on your quest. There are quiet revolutionaries on more than three continents who will be happy to provide advice.

If you have a question – or if you’d like to debate a contentious point – visit the Forum at www.salesprocessengineering.net and create a new thread (comment) with your question.

Additionally, consider attending our invitation-only webinar, Beyond The Machine. This webinar is designed to give practical implementation advice to people who have just read this book. In particular, it focusses on:

- Seven different applications of SPE (there’s a strong likelihood that one of these models – or a blend of two of them – will the right one for your business

- Common implementation roadblocks – and how to circumvent them

If you’d like an invitation, use the Contact form to request one (don’t put your email address in comments).

[i] Eli Goldratt defines information as the answer to the question asked. Absent the question, the data is … just data!

[ii] You might want to start with Developing Products in Half the Time, by Smith and Reinertsen.

[iii] For your amusement, here’s an example of a bridge that I internalized years ago (when I was selling insurance) and that I still can’t prevent myself from using today: In order to determine if our service is going to make sense for your organization, I need to get your answers to three simple questions; do you mind if I go-ahead and ask them?

[i] If we encounter line managers, these people tend to be supervising customer service or inside sales teams and, more often than not, they are very capable.